Rolls Royce Aircraft Engine Manual

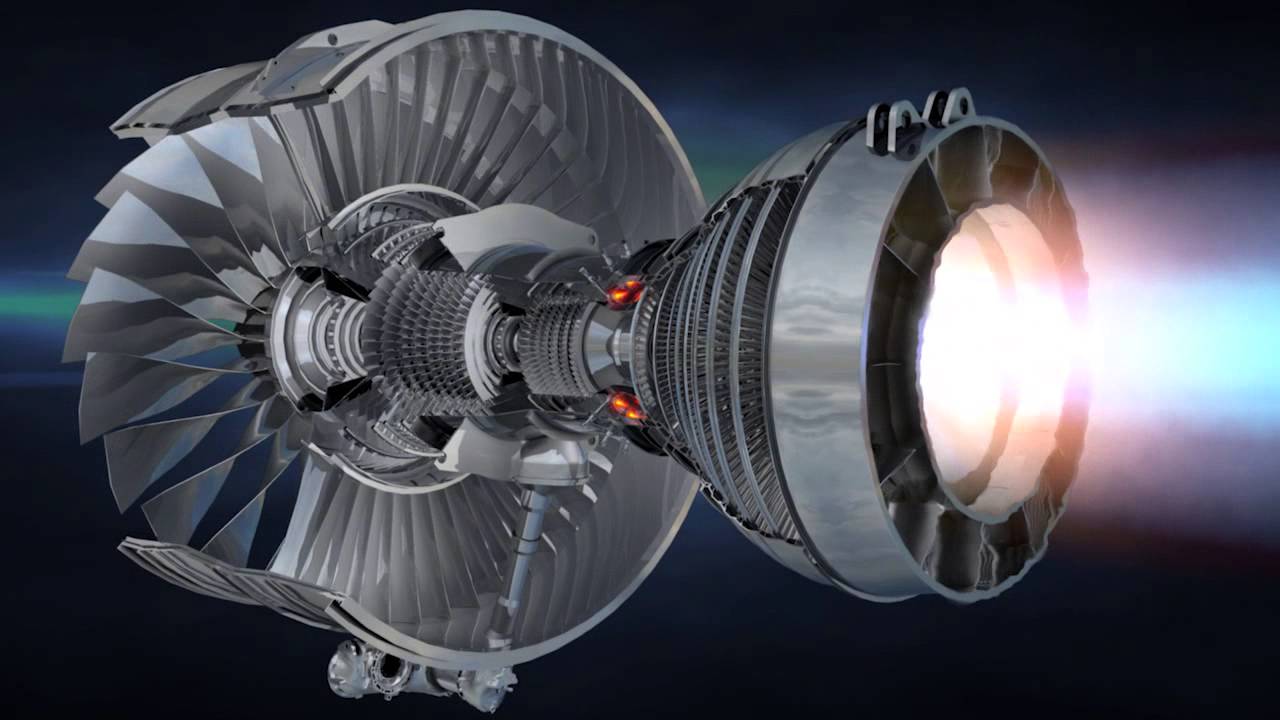

- In achieving its world record time on wing of over 40,500 hours, demonstrated the superior performance of the Rolls-Royce three-shaft engine. By far the quietest engine on the 757-200 and -300 (6dB more margin to Chapter 3), with ample margin to the Chapter 4 limits - favouring extended operation from noise-sensitive airfields during curfew.

- Rolls-Royce June 1, 1993 501-D22,A,C,G, and 501-D36 INDEX Revised Aug 8, 2019 PAGE 3 OF 4 COIL No. Subject Published Revised 1059 Compressor Wheel MPI Inspection 03-01-90 (No Effectivity For D36 Engine) 1060 Critical Shafting Inspection for Grinding Burns 02-28-91 (No Effectivity For D36 Engine).

Rolls-Royce produced a range of piston engine types for aircraft use in the first half of the 20th Century. Production of own-design engines ceased in 1955 with the last versions of the Griffon; licensed production of Teledyne Continental Motorsgeneral aviation engines was carried out by the company in the 1960s and 1970s.

Rolls-Royce Aircraft Engines Using FlightMessenger to Monitor Maintenance Needs. Materi rumus pengambilan sampel isaac and michael pdf. As part of its 24/7 monitoring service, Rolls-Royce will use the EHM data distributed by SITAONAIR's AIRCOM.

Examples of Rolls-Royce aircraft piston engine types remain airworthy today with many more on public display in museums.

WWI[edit]

In 1915, the Eagle, Falcon, and Hawk engines were developed in response to wartime needs. The Eagle was very successful, especially for bombers. It was scaled down by a factor of 5:4 to make the Falcon or by deleting one bank of its V12 cylinders to make the Hawk. The smaller engines were intended for fighter aircraft. Subsequently, it was enlarged to make the Condor which saw use in airships.[1]

Inter-war years[edit]

The Kestrel was a post-war redesign of the Eagle featuring wet cylinder liners in (two) common cylinder blocks. It was developed into the superchargedPeregrine and later the Goshawk.[2]

Developed concurrently with the Kestrel was the unusual Rolls-Royce Eagle XVIX engine that was cancelled in favour of the Kestrel despite performing well on the test stand.

The Buzzard was an enlargement of the Kestrel [3] of Condor size, developed in its most extreme form into the Rolls-Royce R racing engine used for the Schneider Trophy competition.[4]

The Vulture of 1939 was essentially two Peregrines on a common crankshaft in an X-24 configuration, both of these types being deemed unsuccessful.[5]

Rolls Royce Aircraft Engine Manuals

WWII and beyond[edit]

The Rolls-Royce Merlin, and later the development of the Buzzard, the Rolls-Royce Griffon were the two most successful designs for Rolls-Royce to serve in the Second World War, the Merlin powering RAF fighters the Hawker Hurricane, Supermarine Spitfire, fighter/bomber de Havilland Mosquito, Lancaster and Halifax heavy bombers and also allied aircraft such as the American P-51 Mustang and some marks of Kittyhawk.

Experimental engines were developed as alternatives for high performance aircraft such as the H-24 configuration Rolls-Royce Eagle 22,[6] the two-strokeRolls-Royce Crecy[7] and the Rolls-Royce Pennine[8] and Rolls-Royce Exe, the Exe being the only one of these last three engines to fly.[9] However the successful development of the Merlin and Griffon, and the introduction of jet engines precluded significant production of these types.

Production of Rolls-Royce designed aircraft piston engines ceased in 1955 with the last variants of the Griffon.[10] Between 1961 and 1981 Rolls-Royce was licensed to build the Teledyne Continental range of light aircraft piston engines including the Continental O-520.[11]

Survivors[edit]

As of 2017 examples of the Falcon, Griffon, Kestrel and Merlin remain airworthy.[12]

Engines on display[edit]

Various types of Rolls-Royce aircraft piston engines are on public display at the following museums:

Chronological list[edit]

See also[edit]

Related lists

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^Lumsden 2003, pp.183-190.

- ^Lumsden 2003, pp.190-198.

- ^Lumsden 2003, p.198.

- ^Lumsden 2003, p.199.

- ^Lumsden 2003, p.200.

- ^Lumsden 2003, p.221.

- ^Nahum, Foster-Pegg, Birch 2004.

- ^Rubbra 1990, p.148.

- ^Lumsden 2003, p.201.

- ^Lumsden 2003, p.218.

- ^Gunston 1989, p.42.

- ^See individual articles for details

- ^By first run date

Bibliography[edit]

- Gunston, Bill. World Encyclopedia of Aero Engines. Cambridge, England. Patrick Stephens Limited, 1989. ISBN1-85260-163-9

- Nahum, A., Foster-Pegg, R.W., Birch, D. The Rolls-Royce Crecy, Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust. Derby, England. 1994 ISBN1-872922-05-8

- Lumsden, Alec. British Piston Engines and their Aircraft. Marlborough, Wiltshire: Airlife Publishing, 2003. ISBN1-85310-294-6.

- Rubbra, A.A. Rolls-Royce Piston Aero Engines - a designer remembers: Historical Series no 16 :Rolls Royce Heritage Trust, 1990. ISBN1-872922-00-7

Further reading[edit]

Rolls Royce Aircraft Engine Manual Transmission

- Bill Gunston, Development of Piston Aero Engines. Cambridge, England. Patrick Stephens Limited, 2006. ISBN0-7509-4478-1

- Bill Gunston, Rolls-Royce Aero Engines, Patrick Stephens Limited (Haynes Group) ISBN1-85260-037-3

- Sir Stanley Hooker, Not Much of an Engineer, Airlife Publishing, ISBN0-906393-35-3

- Pugh, Peter. The Magic of a Name - The Rolls-Royce Story - The First 40 Years. Cambridge, England. Icon Books Ltd, 2000. ISBN1-84046-151-9

External links[edit]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rolls-Royce piston aircraft engines. |

- 'From Eagle to Merlin' a 1939 Flight article